Honestly, the more I find out about phonology the more I realize I don’t know and the weirder seemingly simple things get. But that’s the joy of this whole endeavour, isn’t it? To explore and discover new things.

Sorry this post took so long — I also ended up working on a lot of aspects of this conlanging/worldbuilding project at once, and I’ve been spending some time to look closely into Inuktitut as well!

Anyways, let’s get on to the main topic for today: vowels.

What is a vowel?

Memes aside, each of these covers part of the whole truth, and offers a different way of thinking about vowels. Let’s check each of them out!

1. AEIOU and sometimes Y

If you haven’t studied linguistics before, you might be surprised that there’s more than just five vowel sounds. This is because English also uses the word “vowel” to mean the written letters aeiou and sometimes y, which is not a very helpful definition phonologically, because in reality, English has a lot of distinct vowel sounds! For example, try speaking this sentence:

Who would know aught of art, must learn, act, and then take his ease.

| Who | would | know | aught | of | art | must | learn | act | and | then | take | his | ease |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hu | wʊd | noʊ | ɑt | ʌv | ɑrt | mʌst | lɜrn | ækt | ænd | ðɛn | teɪk | hɪz | iz |

Clearly (depending on your dialect), the “o” in “who” (/hu/) and the “o” in “of” (/ʌv/) make entirely different sounds, as do the “a” in “art” /ɑrt/ and the “a” in “act” /ækt/. If you’re super observant, you might also notice that some of these words are composed of multiple vowel sounds, such as “know” (noʊ) and “take” (teɪk). These are called diphthongs, where a combination of vowel sounds both occupy the nucleus of a syllable (more on this later).

So I might have lied a bit about all of these definitions being somewhat correct — this definition of vowels (if we’re talking about sounds and not letters) is basically just wrong. So how can we actually get a better sense of what vowel sounds are?

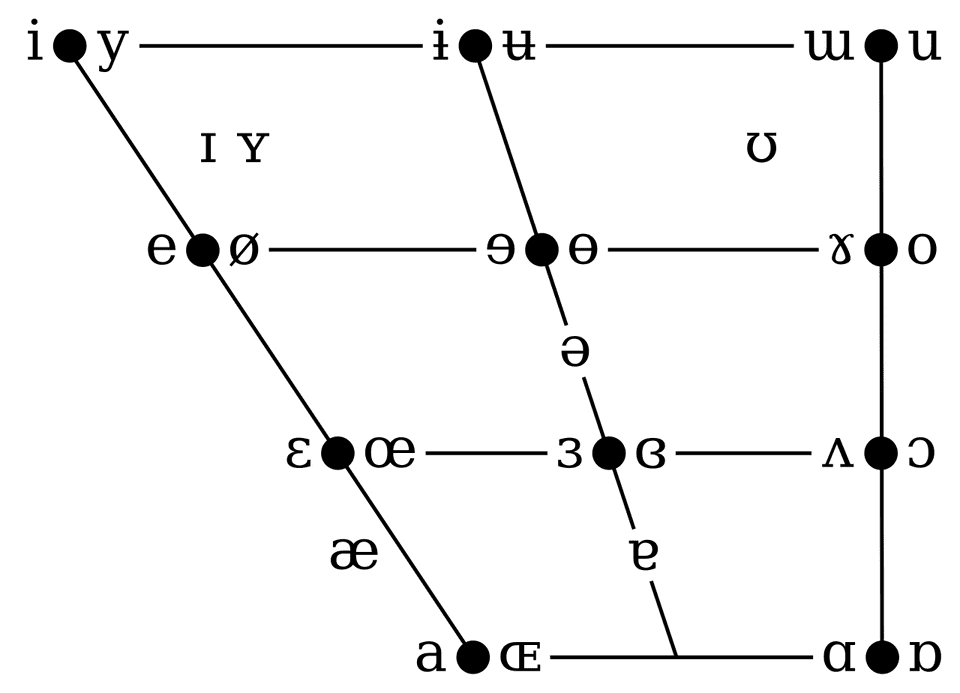

2. An open vowel tract with the tongue in a certain position

Phonetically, a vowel sound is one produced with an open vocal tract, where you don’t block off air like you do with consonants. But what actually makes one vowel sound different from another?

Try saying that above sentence again, but this time, pay careful attention to the position of your tongue. You should notice that you can produce different vowel sounds by placing your tongue in different positions!

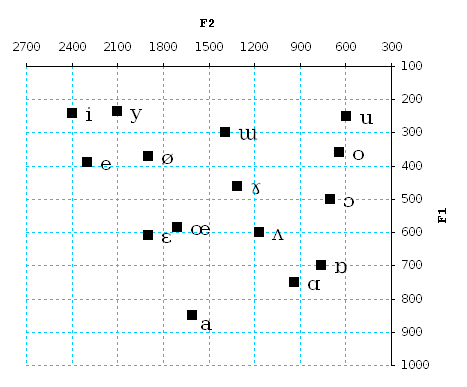

This is how the IPA vowel chart is organized! Left-to-right indicates how “front” or “back” your tongue is, and top-down indicates how high or low your tongue is. (Vowels where the tongue is high are also called close vowels because the mouth cavity is closed, and ones where the tongue is low are called open vowels because your mouth is relatively open.)

Interestingly, all languages thus far use height to distinguish between vowels, but not all languages have distinctions between front and back vowels or rounded/unrounded ones!

Where English dialects typically differ is in their vowels. British English (“Received Pronunciation”, or “RP”) has about 13 monophthongs, 9 diphthongs, and 5 triphthongs (like in “hour” /aʊə/), while General American (GA) has about 13 monophthongs and 3 diphthongs, along with about 7 R-coloured vowels, and Australian English has about 14 monophthongs and 6 diphthongs.

This is a ton compared to other languages like Japanese, which has the five monophthongs a, e, i, o, u, or the extinct Ubykh language with only two vowels /a/ and /ə/ (but also 80 consonants soooo… yeah). On the other hand, it’s nothing compared to the Bahnaric languages spoken in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos, with up to 55 distinct vowel sounds!

So you might think that’s it for vowels, and actually, it ends up being close enough to not make much of a difference, and this definition is still widely used. But in reality, the science of how our brain understands vowels ends up actually being way cooler, and the whole thing with the position of the tongue just happens to be a really good everyday approximation! Sort of like how classical Newtonian mechanics happens to be a really good everyday approximation for the theory of relativity. So let’s dive in to the real nitty-gritty, shall we?

3. Musical intervals

First of all, jump to 8:00 in the following video to hear some super cool overtone singing of “Amazing Grace”:

What does this have to do with vowels, you might ask? Well, the theory behind how our brain interprets vowels is the same concept that allows throat singers/overtone singers like the guy in the video to sing multiple notes at once! 🤯

(If you’re having trouble hearing the overtones, check out this slightly edited version I made that emphasizes the overtones slightly more.)

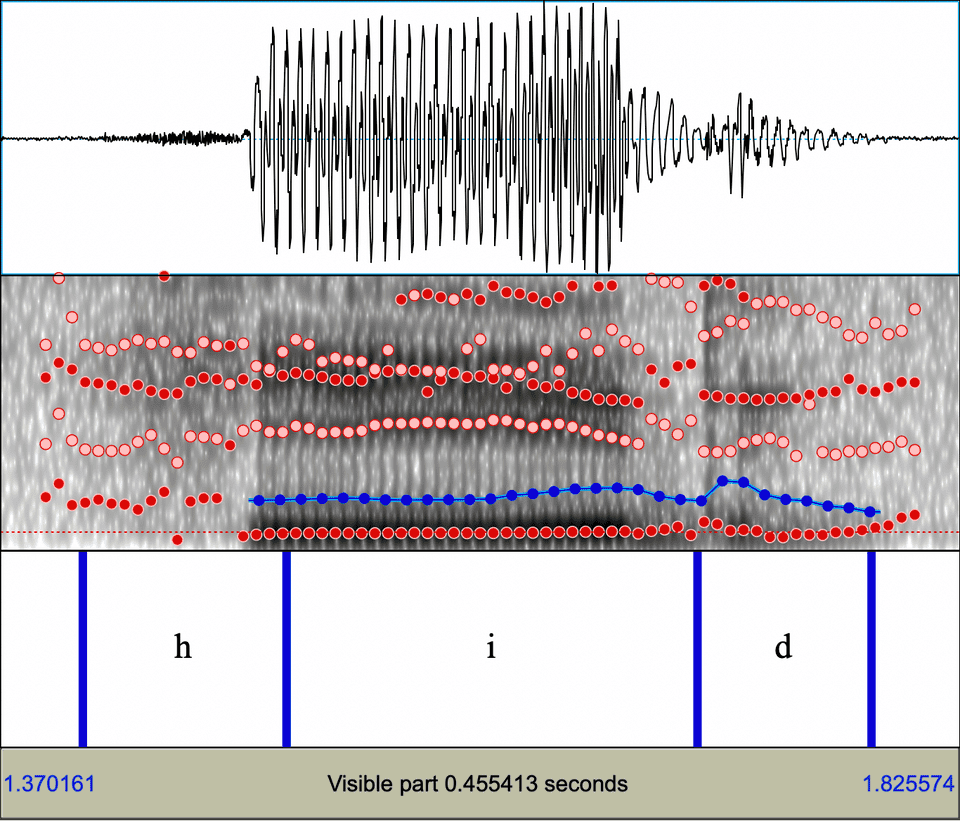

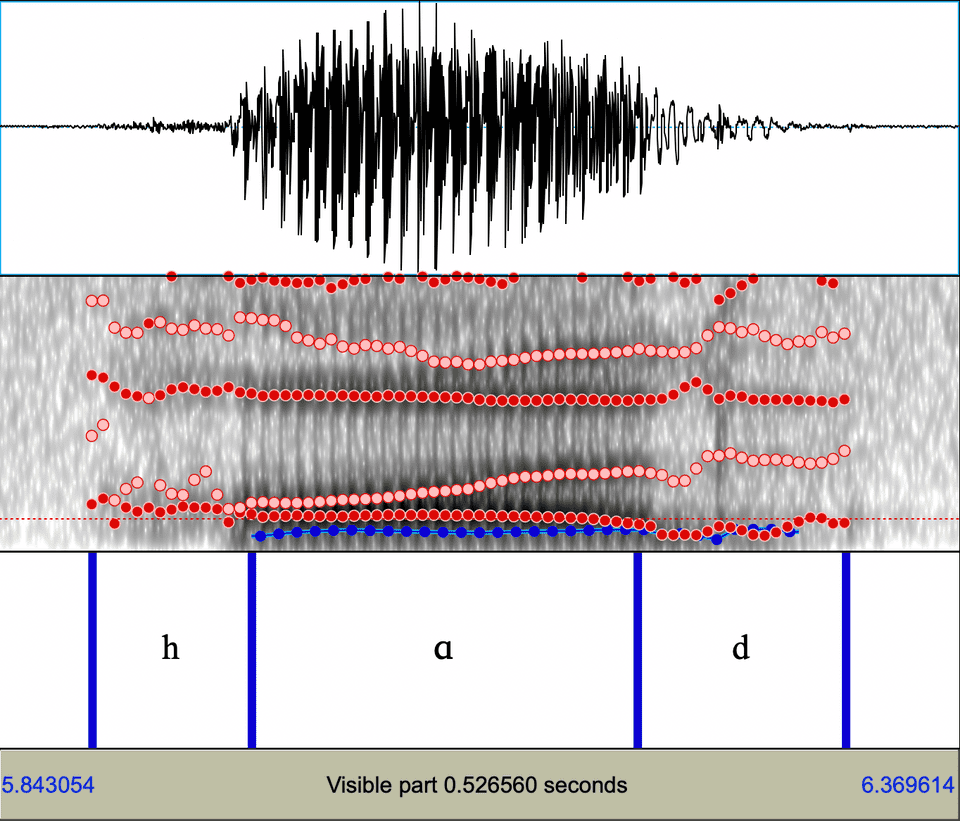

Quick physics recap — Essentially, all sound is just made of vibrating particles. When we make a sound, we’re actually just using our vocal chords to vibrate the air around us! Not just at one frequency, though, but at a combination of different frequencies,2 sort of like in a chord in music! (I admit the analogy is a bit far-fetched, but it gets the idea across.) We can visualize these frequencies over time using a type of chart called a spectrogram, where the x-axis represents time, and the y-axis represents frequency/pitch. For example, here’s two spectrograms of me saying “heed” [hid] and “hawed” [hɑd].

The program Praat (which I might walk through in a future post) identifies these certain bands of frequencies that your voice emphasizes. Those are the stripes of red and pink dots. Each of these frequencies is called a formant, and they’re numbered from lowest to highest.

For example, in the “heed” diagram (top/left), the lowest formant (F1) is at about 360 Hz, the second-lowest (F2) is at about 2300 Hz, the third-lowest (F3) is at around 3020 Hz, and the fourth-lowest (F4) is at around 3530 Hz.

In the “hawed” diagram (bottom/right), F1 is at about 670 Hz, F2 averages at about 1200 Hz, F3 is at about 2815 Hz, and F4 is at about 3650 Hz.

The craziest thing is that if you graph F1, increasing from top to bottom on the y-axis, against F2, increasing from right to left on the x-axis — think quadrant III on the Cartesian plane — it lines up super closely with the previous idea of the position of the tongue in the mouth, even given rounding! Compare the IPA chart with this graph of the average vowel formants:

In other words, F1 increases in pitch as your mouth opens, and F2 increases in pitch as your tongue moves from back to front. In other words, /i/ is characterized by a low F1 (360 Hz) and a high F2 (2300 Hz), while /ɑ/ is at a higher F1 (670 Hz) and a lower F2 (1200 Hz). (Values in brackets are mine, see above for average.) That’s why the IPA vowel chart, and telling people to move their tongue towards certain places, works, despite not being fully the whole picture!

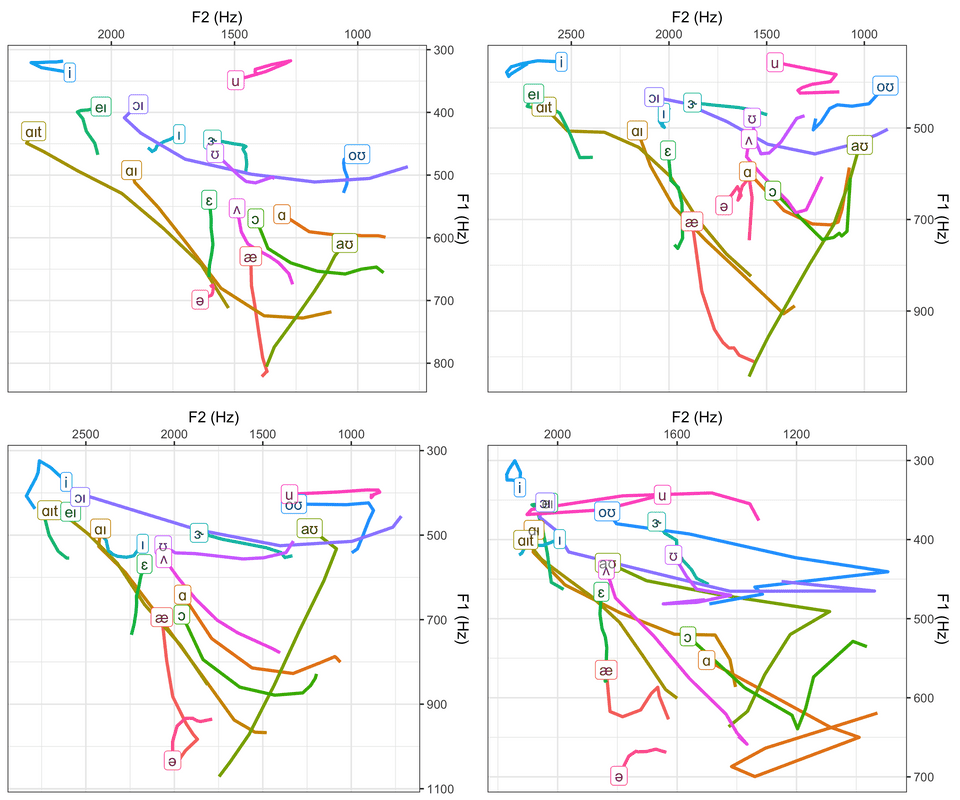

We can analyze individuals’ vowels by graphing them in this way. Here’s the vowel charts of me and three of my classmates:

Theoretically, there should be a third dimension of time, but for convenience, time is squashed down into the plane and movement is indicated by lines with the letters appearing at the final position of the sound.

There’s a couple interesting things to notice. Firstly, even monophthongs don’t actually stay in the exact same place, and the formants will actually drift considerably (although this might just be a consequence of the consonants at the onset and coda (start and end) of the syllable). Secondly, check out just how different the charts are! I personally find it super incredible that despite differences in accent, somehow we can still use these sounds to distinguish between different words.

All of this detailed sound and physics stuff resides in the field of auditory phonetics, the science of how we actually hear these sounds and decipher them. But finally, to get the whole picture of vowels, we need to consider not just what they sound like, but also how those sounds are used in language. And for that, let’s turn to some phonology.

4. A sound that forms the nucleus of a syllable

This would be the phonological definition of a vowel: a sound that occupies in the centre, or nucleus, of a syllable. This definition helps us distinguish vowels from approximants like [j] and [w], which, like vowel sounds, don’t restrict the air much, but they can’t form the centre of a nucleus (in English), which is why they’re considered as consonants and not vowels (in English).

Some linguistics use different terms for phonemic vowels (sounds allowed at the centre of a nucleus) and phonetic vowels (sounds with an open vowel tract), calling the latter “vocoids” instead. For example, [j] would be considered a vocoid but not a vowel, since it’s pronounced with mostly open airflow but can’t exist in the nucleus of a syllable.1

We can also have it the other way around: sounds that are phonetic consonants, but can exist in the nucleus of a syllable. These are called syllabic consonants and are usually approximants like [j], nasals like [m] and [n], or liquid consonants like [r] and [l]. These are common in Czech and Slovak, and also appear in the English “even” [ˈiːvn̩], “awful” [ˈɔːfɫ̩], and “rhythm” [ˈɹɪðm̩], depending on your dialect. (Personally in my dialect, I stick an extra vowel in there to make it fit, i.e. [ˈɹɪðəm̩].) In an IPA transcription, a syllabic consonant is indicated by a tick underneath it.

This means you can construct entire sentences without phonetic vowels! The current longest such sentence in Czech is:

[ʃkr̩t pl̩x zml̩x br̩t pl̩n skvr̩n zmr̩f pr̩f ɦr̩t st͡svrn̩kl̩ zbr̩st skr̩s tr̩s xr̩p fkr̩s vr̩p ml̩s mr̩x sr̩n t͡ʃtvrdɦr̩st zr̩n]

In English, this means something like “Stingy dormouse from Brdy mountains fogs full of manure spots firstly proudly shrinked a quarter of handful seeds, a delicacy for mean does, from brakes through bunch of Centaurea flowers into scrub of willows.” Fun!

Other ways vowels change

So there! We’ve gone through four different perspectives and ways to define a vowel. But aside from just the vowel sound itself, there’s a ton of other ways to modify and add to vowel sounds, many of which actually make a phonemic difference in world languages! And what’s more, English lacks most of these, so there’s a good chance you might not have heard of some of these before! Let’s dive in.

Vowel length

Some languages, including Latin, Arabic, and many North American languages including Inuktut and Mi’kmaq, distinguish vowel length phonemically. For example, in Japanese, いいえ “iie” [iːe] is “no”, while 家 (“ie”) means “house” or “home”. The Dinka language, found in South Sudan, actually distinguishes between three distinct vowel lengths!

cól ‘mouse’

cǒol ‘charcoal’

còool ‘pieces of charcoal’

English tends to have longer vowels before voiced consonants (e.g. “bad”) and shorter vowels before unvoiced consonants (e.g. “bat”), although this doesn’t serve a phonemic purpose. The “short/long” pronunciation of the English letters aeiou that they teach in elementary school has nothing to do with actual vowel length; it simply helps to protect innocent children from the monstrosity that is the English vowel system.

Tone

Tone is, from my perspective in an English-speaking country, woefully one of the most under-appreciated features of language. Despite being found in about 42% of world languages or even up to 70%, it seems that many people don’t understand that pitch can actually play a role in differentiating words, and in my opinion, it’s one of the most interesting and beautiful features a language can have. It’s found most commonly in East and Southeast Asia, the Pacific, Africa, and the Americas.

A common misconception is that tone is equivalent to the way we raise our pitch towards the end of questions in English. This is a totally different phenomenon called intonation, which is universal to all language, and doesn’t actually change the meaning of the words in a sentence.

- For example, consider me saying “The weather is nice today!” and “Is the weather nice today?” Though my pitch might be falling towards the end in the first sentence and rising towards the end in the second, the word “today” stays the same.

- This is different from tone, where the pitch is rising or falling can actually distinguish between words, just like two different vowel or consonant sounds.

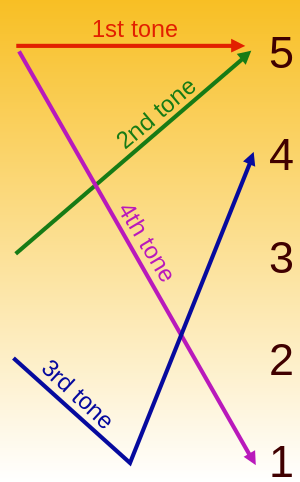

For example, most dialects of Mandarin Chinese have four (plus one) tones: high, rising, low, and falling. The typical example in Chinese is (in pinyin) mā, má, mǎ, mà, which might mean “mother”, “numb”, “horse”, and “scold”. (I say “might” because in Chinese there are a lot of homophones, words that sound the same.) Chinese also has a fifth “neutral” tone, which changes based on the tone of the previous word.

Typically, we analyse contour tones, where the pitch changes throughout the syllable or word, by considering five levels of pitch and looking at how the voice bends. Here’s a diagram of the contour tones of Mandarin:

Notice how the change in pitch matches the marks in the pinyin (mā, má, mǎ, mà)? So to sound out a word based on pinyin, you can just move your pitch based on the shape of the diacritic!

Perhaps confusingly, the IPA uses the same symbols to indicate tone, but they indicate different things. In the IPA, a rising tone is marked /ǎ/, a falling tone is marked /â/, a high tone is marked /á/, and a low tone is marked /à/. Another way to mark tone is through the IPA tone letters, ˩˨˧˦˥, which correspond to the five levels of pitch in the diagram from low to high. E.g. the Mandarin falling tone might be marked ˥˩.

Just as a demonstration of tones to the extreme, consider “Lion-Eating Poet in the Stone Den”, a poem written in the 1930s by Yuen Ren Chao in which he only uses tone to differentiate between words!

| Simplified | Traditional | Pinyin | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| 《施氏食狮史》 | 《施氏食獅史》 | « Shī Shì shí shī shǐ » | « Lion-Eating Poet in the Stone Den » |

| 石室诗士施氏,嗜狮,誓食十狮。 | 石室詩士施氏,嗜獅,誓食十獅。 | Shíshì shīshì Shī Shì, shì shī, shì shí shí shī. | In a stone den was a poet called Shi Shi, who was a lion addict, and had resolved to eat ten lions. |

| 氏时时适市视狮。 | 氏時時適市視獅。 | Shì shíshí shì shì shì shī. | He often went to the market to look for lions. |

| 十时,适十狮适市。 | 十時,適十獅適市。 | Shí shí, shì shí shī shì shì. | At ten o’clock, ten lions had just arrived at the market. |

| 是时,适施氏适市。 | 是時,適施氏適市。 | Shì shí, shì Shī Shì shì shì. | At that time, Shi had just arrived at the market. |

| 氏视是十狮,恃矢势,使是十狮逝世。 | 氏視是十獅,恃矢勢,使是十獅逝世。 | Shì shì shì shí shī, shì shǐ shì, shǐ shì shí shī shìshì. | He saw those ten lions, and using his trusty arrows, caused the ten lions to die. |

| 氏拾是十狮尸,适石室。 | 氏拾是十獅屍,適石室。 | Shì shí shì shí shī shī, shì shíshì. | He brought the corpses of the ten lions to the stone den. |

| 石室湿,氏使侍拭石室。 | 石室濕,氏使侍拭石室。 | Shíshì shī, Shì shǐ shì shì shíshì. | The stone den was damp. He asked his servants to wipe it. |

| 石室拭,氏始试食是十狮。 | 石室拭,氏始試食是十獅。 | Shíshì shì, Shì shǐ shì shí shì shí shī. | After the stone den was wiped, he tried to eat those ten lions. |

| 食时,始识是十狮尸,实十石狮尸。 | 食時,始識是十獅屍,實十石獅屍。 | Shí shí, shǐ shí shì shí shī shī, shí shí shí shī shī. | When he ate, he realized that these ten lions were in fact ten stone lion corpses. |

| 试释是事。 | 試釋是事。 | Shì shì shì shì. | Try to explain this matter. |

Don’t worry, I can assure you that spoken aloud, this is just as unintelligible to me as it is to you. Check out “James while John had had had had had had had had had had had a better effect on the teacher” and “Buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo buffalo buffalo Buffalo buffalo” for English examples of antanaclasis, the repeated use of a single word or phrase in multiple senses.

Aside from contour tone, there’s also register tone in some languages such as Swedish, Norwegian, and many Bantu languages, where instead of applying to individual syllables, tone can apply to entire words. For example, “bønner” (“beans”) and “bønder” (“farmers”) are both pronounced /bœnər/ and are distinguished only by pitch. Most tonal languages (not Standard Mandarin, though) actually use a combination of both! For example, Cantonese has both a medium rising tone (3-5 on the pitch scale) and a low rising tone (1–3 on the pitch scale).

Another interesting facet of tones is tone sandhi. Sandhi is a more general term describing what happens to sounds at boundaries between words or morphemes, and I’ll talk more about it in the post on phonotactics. Specifically in this case, tones can have different pronunciations based on their neighboring environment. For example, in Chinese, if two low tones are next to each other (e.g. “nǐ hǎo”), the first one is typically pronounced as a rising tone instead (“ní hǎo”).

Only just recently, languages have been researched that use tone not only as a phonological tool, but as a tool for inflection! I haven’t talked about inflection yet — I’m super excited to do so when we get to morphology — but essentially, it means modifying a word to indicate additional information, e.g. in English “I eat” vs “he eats”. For example, in Tlatepuzco Chinantec, a language from Southern Mexico, tone distinguishes mood, person, and number: [tøʔ] pronounced with a low tone might mean “I called”, while pronounced with a low rising tone might mean “I was calling.” See Tone and inflection: An introduction by Palancar and Léonard (2015) for details.

Using tone for inflection would be so cool to include in a conlang, but I’m not sure if I want to include tone yet just because it would make it waaay harder to learn for people who don’t speak tonal languages already. But who knows?

Nasalization

This determines whether or not air passes through the nasal cavity as well as through the mouth. For example, in French, nasalization is phonemic and marks the difference between “main” /mɛ̃/ (hand) or “mets” /mɛ/ (a dish in cooking, or the first or second person singular conjugation of mettre, to place). A number of languages use phonemic nasalization, including many Aboriginal languages in the Americas as well as certain dialects of Mandarin.

Voicing

Another distinction is voicing, which works exactly the same way as it does for consonants: essentially, a voiced vowel is one where your vocal chords are vibrating, and unvoiced is where they aren’t.

Vowels, along with nasals and semivowels, are classified as sonorant sounds: sounds that are almost always voiced. But very rarely, there’s also unvoiced vowels, such as in Japanese <u> and <i> in certain environments, e.g. the ending vowel in verbs that end in す “su” often becoming the unvoiced, unrounded back vowel [ɯ̥], e.g. です “desu” [desɯ̥], “to be”.

Most languages with voiceless sounds are found around the Pacific Ocean, as well as in a few other languages including Welsh, Icelandic, and the Austronesian and Eskimo-Aleut languages.

Also included in this category would be other variations that the vocal chord can make, such as breathy voice (more airflow, kind of like a sighing sound), which is used phonemically in the Nguni languages in South Africa, and creaky voice (kind of like the Californian vocal fry), which is used phonemically alongside modal voice (how we usually pronounce vowels) and breathy voice in Jalapa Mazatec, a language from southern Mexico.

Conclusion

Wow, that ended up being waaay longer than I was expecting to. Exciting stuff, though! And all of these features of vowels are definitely factors I’ll need to consider including in my conlang. In my next post, I’ll quickly go through phonotactics, which is the study of how we combine sounds together, and then that’s basically it for our section on phonetics and phonology and we can actually start building the conlang! Thanks for reading, drop me a message if you have feedback, and hope to catch you again soon!

-

However, later research has shown that the airflow is still blocked to a degree — see The Sounds of the World’s Languages by Maddieson and Ladefoged.

↩ -

If this seems counterintuitive, consider musical instruments. When a musician plays a note, you might only hear one sound, but in reality, that sound is composed of a unique set of higher frequencies (aka harmonics) that give each instrument its distinct sound (aka timbre).

If you’re not convinced and you have a (real) piano nearby, you can verify this with a quick experiment. Push down middle C without making sound and hold it there. Then, hold the dampening pedal and quickly hit the C one octave below. Keep your finger down on middle C and let go of the pedal.

You should be able to hear the middle C as if you had played it, when in reality you only played the C an octave below! How did that happen?

When you played the lower C, it generated a series of harmonics that included the frequency of middle C. By holding down the middle C, you allow the string to freely resonate (see this video on how pianos work). Thus, the vibrating particles in the air, caused by the lower C, in turn jiggle the middle C string at its precise frequency, causing it to resonate!

You can try holding down different keys above the low C to get a sense of which harmonics it generates! If you know some music theory, you might find some interesting patterns.

↩