Bonjour! Long time no see. I’ve been a bit busy and recently landed a tech internship for the summer, which I’m pretty excited about! But that’s enough about me — let’s get onto the conlanging.

So, as per usual, a post which I thought would be simple and straightforward has turned out to be way more in-depth and complex than I expected. I was hoping after going through the basic building blocks of sounds that the next steps would be simple and straightforward, but the more I read, the more I realize how intricate and interwoven linguistics is with other aspects of our world.

At first, my idea of a phonetic inventory was just to pick out the sounds that I thought looked cool and that would fit logically into a pretty regular consonant table. But then, I started reading up on historical linguistics and sound changes, and now all of a sudden I need to actually consider where those sounds come from and how (and maybe why) they’ve developed. Or actually, I mean, that’s more of a story for another day.

So this post is going to be a little bit all over the place. I want to briefly talk about features, how I’m building the phonetic inventory, phonotactics, and graze the surface of historical linguistics. Without further ado, let’s get started!

Features

The main resource I used for this section was Chapter 4 from Bruce Hayes’ Introductory Phonology. This is going to basically be a brief summary of the textbook, and you can read it yourself for more details. I’m also working on a site that you can use to interact with features and sounds, but until then, if you want to do some exploration, there’s also Pheatures, a program developed by UCLA where you can poke around with sound changes and features.

Essentially, features are broad labels we can assign to sounds (aka phones, or, more loosely, segments) and combine together to define specific groups of sounds.

You might ask, well, what’s wrong with the labels we have already, like “vowel” or “consonant”? Those are certainly useful, but the issue is that sound changes usually apply to natural classes of sounds that don’t always line up with the IPA.

For example, let’s consider the feature [sonorant]. For each feature, we usually want to look at the sounds which “have” it, written as [+sonorant], and the sounds which don’t have it, labelled [-sonorant]. In this case, [-sonorant] consists of stops, affricates, and fricatives (aka obstruents), while [+sonorant] is everything else. Here’s some evidence that [sonorant] is a feature that defines natural classes:

- In Japanese, Swahili, Spanish, and others, [-sonorant] sounds can contrast in voicing (e.g. [b], [+voice] vs [p], [-voice]) while [+sonorant] sounds are usually [+voice];

- In French, Catalan, Russian, and others, there’s a rule where [-sonorant] sounds will assimilate to match the voicing of a following consonant;

- In German, Dutch, Polish, and others, [-sonorant] sounds are devoiced [-voice] at the end of a word, aka “final devoicing”;

- In Lithuanian, some dialects of Greek, and certain other tonal languages, only syllables ending in [+sonorant] consonants can have contrasting rising and falling tones.

These examples demonstrate that [+sonorant] and [-sonorant] are natural classes, so we should have a feature [sonorant] that allows us to classify them as such.

List of features

The features required to distinguish between natural classes will vary from language to language. Hayes describes the following general list of 30 features:

- [syllabic], [consonantal], [approximant], and [sonorant], used to describe the sonority hierarchy of vowels > glides > liquids > nasals > obstruents;

- [continuant] and [delayed release], used for distinguishing stops, fricatives, and affricates;

- [trill]s and [tap]s;

- [front] and [back] for distinguishing vowel backness;

- [high], [low], and [tense] for describing vowel height;

- [Advanced Tongue Root], known as [ATR], for describing the root of the tongue in vowel pronunciation;

- [labial] for sounds made with the lips, which can be further detailed by [labiodental] and [round] (which can also apply to vowels);

- [coronal] for sounds made with the tongue tip/blade, which can be further specified by [anterior], [distributed], [strident], and [lateral];

- [dorsal] for sounds made with the body of the tongue, which is also the key articulator for vowels, and so dorsal consonants can also be specified using [front], [back], [high], and [low];

- [voice], [spread glottis], [constricted glottis], and [implosive], known as the pharyngeal features;

- [long], [nasal], and [stress], which can apply to both vowels and consonants, although [stress] is arguably more of a feature of syllables and not segments.

Most of these have more technical definitions than what I’ve given. I’m currently in the works of building a web app to help play around with these features, but since it keeps crashing, I’ll hold off and let you know when it’s actually ready!

Phonetic inventory behind the scenes

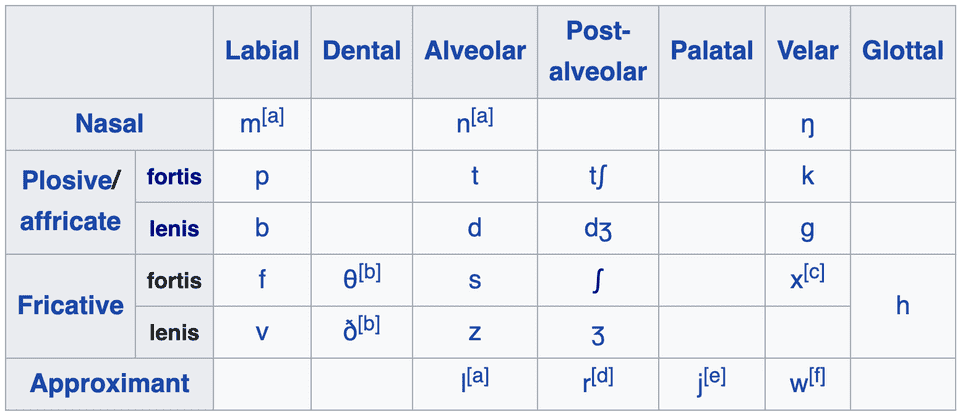

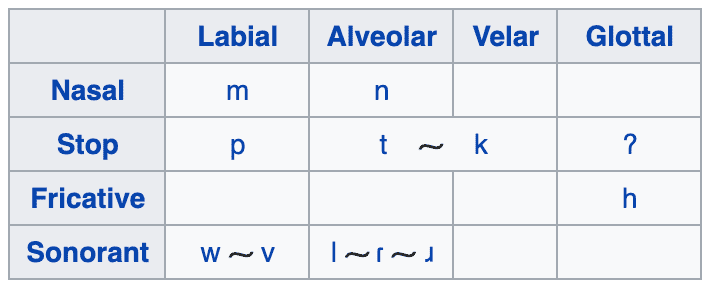

So the sounds in natural languages aren’t just picked randomly out of a box. In terms of consonants, they usually come in series of sounds in the same place or manner. We call an inventory that has a lot of these series “symmetric”. For example, an inventory like

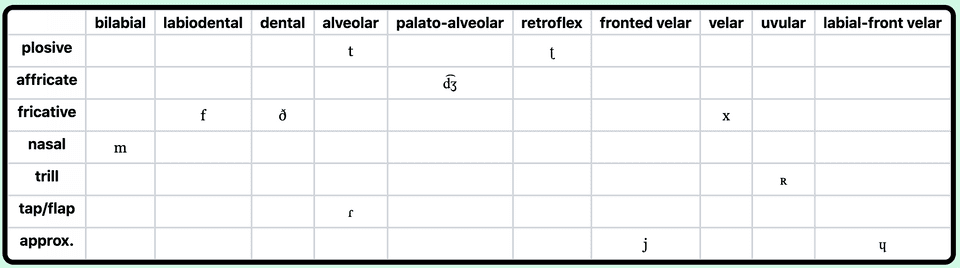

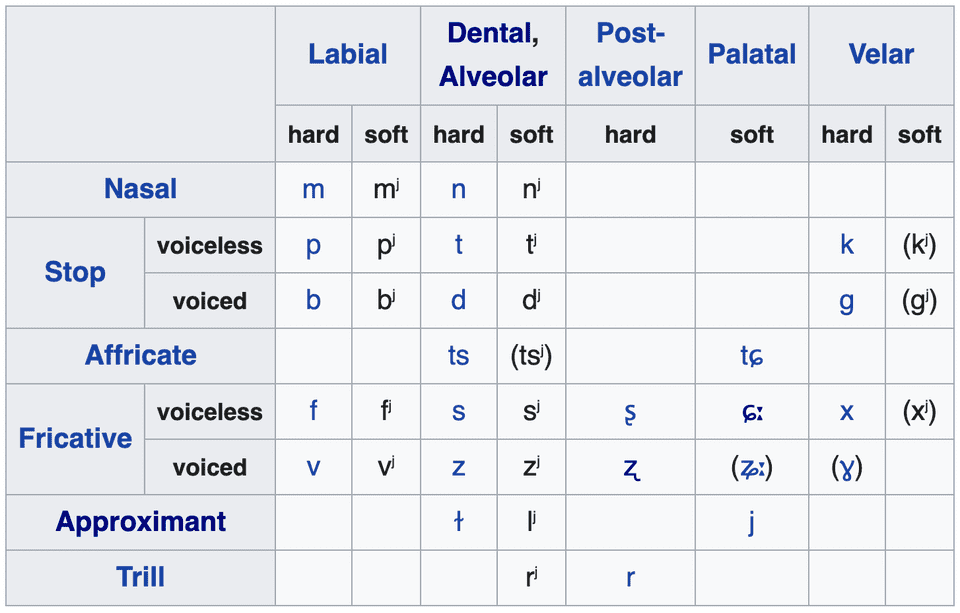

would be quite asymmetric and unnaturalistic; you wouldn’t expect to see that in a natlang. On the other hand, if you look at the inventories of a few natural languages, e.g. Russian, English, and Hawaiian below, you’ll see that they all have a certain level of symmetry to them:

Another consideration is that not all sounds occur equally often. You can find a list of the frequencies of sounds using the UCLA Phonological Segment Inventory Database, aka the UPSID, a super valuable phonology resource.1 According to UPSID, the ten most frequent consonants and vowels are (out of 451 surveyed languages):

| consonant sound | m | k | j | p | w | b | h | g | ŋ | ʔ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| frequency | 94.2 | 89.4 | 83.8 | 83.2 | 73.6 | 63.6 | 61.9 | 56.1 | 52.6 | 47.9 |

| vowel sound | i | a | u | ɛ | o̞ | e̞ | ɔ | o | e | ã |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| frequency | 87.1 | 86.9 | 81.8 | 41.2 | 40.1 | 37.5 | 35.9 | 29.0 | 27.5 | 18.4 |

UPSID also shows us that the total number of segments/phones in a language tends to be around 29-31, although some languages contain as few as 11 (Pirahã and Central Rotokas) or up to an alleged 141 (!Xun)2

Another resource for looking into regional variation in phonology and other language features is The World Atlas of Language Structures, aka WALS. If we take a look at consonant inventories of languages around the world, we can see that Native American languages on the West Coast (e.g. Squamish, Haida, Tlingit), the Kartvelian languages in the Caucases (e.g. Georgian), and the Khoisan languages of southern Africa (e.g. !Xóõ and !Xun) have noticeably large consonant inventories, while most Austronesian languages (e.g. Dyirbal) and many languages in northern South America (e.g. Wayuu and Warao) have smaller inventories of around 6-14 consonants.

Phonotactics

So phonotactics is the study of how sounds can come together in a language. Different languages will have different restrictions, which will greatly shape the way the language sounds. Take, for example, the sentence “Ni hui shuo zhongwen ma?” Even if you don’t speak Chinese, you might be able to identify it as Mandarin because of the way the syllables are structured.

A syllable is basically a bundle of sounds, consisting of an onset and a rime, which consists of the syllable nucleus (usually a vowel) and the coda. Usually, the nucleus is obligatory in most languages, the coda is optional in some languages and restricted in others, and the onset can be restricted in some languages, optional, or enforced. I haven’t heard of any languages with an enforced coda.

Other systems of organizing timing are also possible, such as morae and stress timing, and languages arguably lie somewhere along a continuum rather than being explicitly one or the other.

Typically, sounds within a syllable will be ordered according to the Sonority Sequencing Principle (SSP). Essentially, just in terms of amplitude, the hierarchy of sounds looks something like this: Vowels > Glides > Liquids > Nasals > Obstruents (fricatives > stops > clicks).

Within a syllable, the amplitude generally increases towards the nucleus and decreases on the sides, such as in the english word “trust”, consisting of an obstruent-liquid-vowel-fricative-stop. The SSP also explains why words like “trend” are allowed while a word like “rtedn” would not be.

While English allows consonant clusters, some languages, such as Hawaiian and most Polynesian languages, forbid them entirely (i.e “CV”, consonant-vowel, phonotactics). Some, like Mandarin, restrict the set of consonants that can cluster (i.e. a maximum syllable of CGVXT, where G can be one of the glides [j, w, ɥ] and X can be one of [n, ŋ, ə̯˞, i̯, u̯], with an additional tone). On the other hand, some languages allow very complex consonant clusters, such as Georgian /ɡvbrdɣvnis/ “he’s plucking us”, which would be analyzed as CCCCCCCCVC.

Awesome, well that just about wraps up phonology for now! I might have another post or two later when it comes to how sounds develop and change over time. Anyways, the next post on the phonology of my conlang (which has a name now!) is already up, go check it out!

-

By the way, if you visit the site, you’ll notice that instead of the IPA, they use an alternative way of transcribing sounds: X-SAMPA, which has the benefit of being able to fit into ASCII encoding / be able to be typed on a typical keyboard.

↩ -

Yes, the exclamation mark is part of the name! I didn’t talk about clicks in my consonants article, where I mostly focused on pulmonic consonants, since I don’t plan to include other ones in my conlang. They’re a separate class of consonants mostly found in southern Africa. You can find more about non-pulmonic consonants at this video by LingSpace.

↩