Hallo Leute! Ich hoffe euch geht’s gut. Here’s the plan:

Since I hope this blog can be a resource for other amateur conlangers, the next few posts will focus mainly on some fundamental linguistics before diving into the actual conlanging. In this post, we’ll start off with an intro to how consonants work! By the end of this, you’ll be an expert on the average human food hole and hopefully be able to decipher funky terms like “voiceless palato-alveolar fricative”. Let’s dive in!

(Most of this article is based on The Sounds of the World’s Languages by Ladefoged and Maddieson, a super comprehensive text I’ve recently started and would highly recommend for an in-depth investigation of phonetics, as well as these three videos in Artifexian’s conlanging series. Definitely check them out if you’re interested in learning more!)

What is phonetics?

Language can be communicated in a number of different ways, such as writing, signing, or, most importantly in this post, speaking. Phonetics is simply the study of how we make these sounds, including how we can analyze and classify them!1 (Not to be confused with phonology, the study of how these sounds are actually organized into a language.)

We call the smallest unit of sound a phone (not to be confused with a phoneme),2 such as [l], [e], and [t] in “let”. To represent these sounds, we use the International Phonetic Alphabet, which has symbols for almost all sounds produced by humans.3 These symbols are summarized in the IPA chart, which this post will hopefully help you understand!

We can categorize these phones as either consonants or vowels. Today, we’ll be talking about consonants, like [r], [p], and [g], which are formed when air from the lungs is blocked off to some degree. Consonants are defined by three main properties:

- Place of articulation,

- Manner of articulation,

- and Voicing.

Let’s get started!

1. Place of articulation

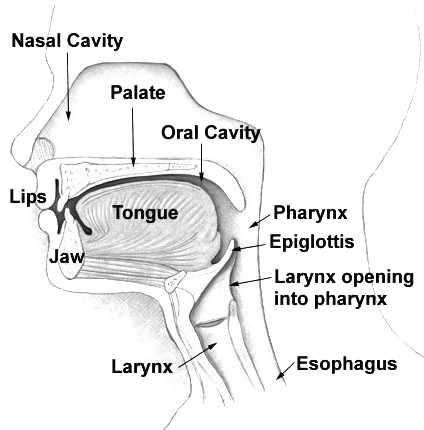

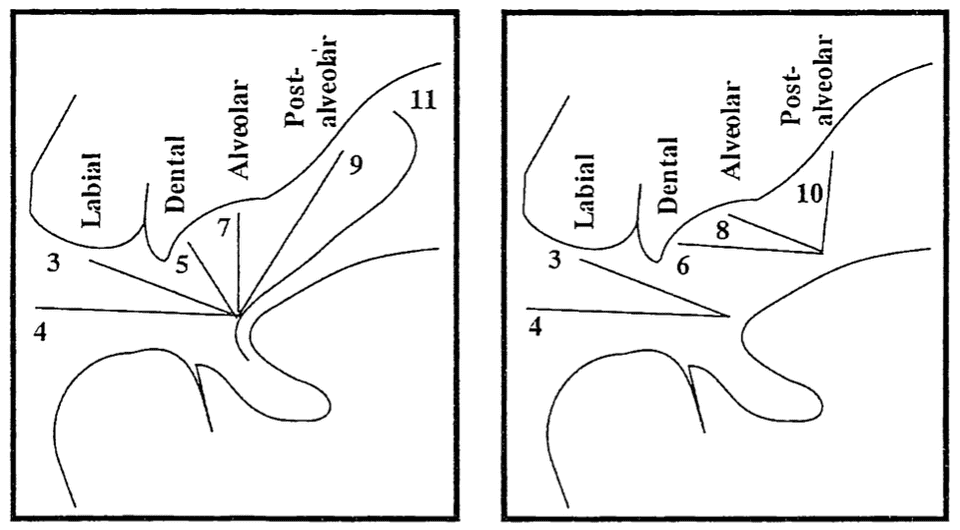

Here’s a cross-section of the human oral cavity:

Firstly — the tongue is huge, isn’t it!?

Anyways, in the above picture, you’ll see a lot of things that can move, and a lot of places they can go. We call the thing that moves the active articulator, and the place it goes the articulatory target region (sometimes called the passive articulator). Together, they form a place of articulation that determines where a consonant is made.

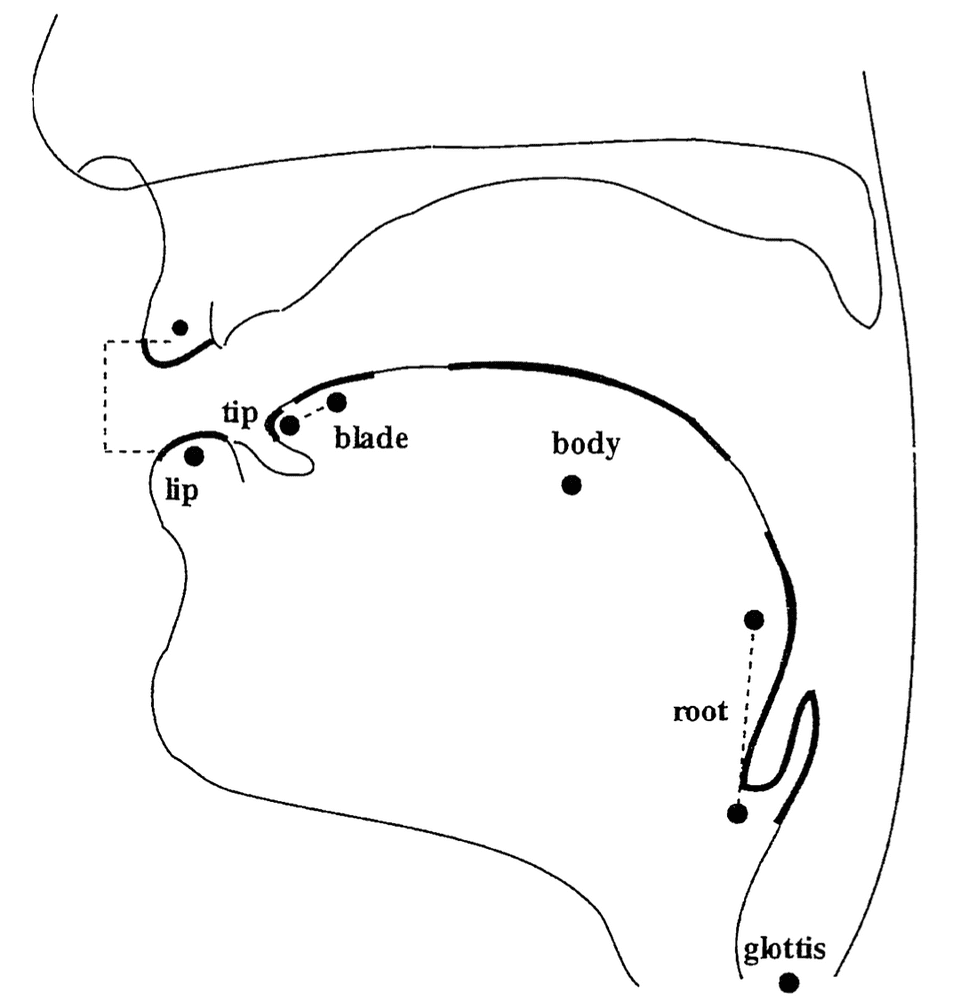

Active articulators

There’s 5 main active articulators, each with a specific name for sounds that use them (and my personal suggestion for a mnemonic to remember their names):

- The lips, which are involved in labial articulations (think “lip”-ial);

-

The tip and blade of the tongue, which make coronal articulations (think of this region as the “corona” / outer part of your tongue). Specifically, there are names for each part of this region:

- Tip of the tongue: apical (think “apex”)

- Underside of the tip: sub-apical

- Blade (the part slightly behind the tip): laminal (“lamina” = a thin plate or scale)

- The body of the tongue, which is involved in dorsal articulations (“dorsal” = near the back, like a fish’s dorsal fin);

- The root of the tongue and the epiglottis, which make radical articulations (“radical” = relating to the root);

- And the glottis, which makes glottal articulations (think of the British pronunciation of “glottal” as “glo-al” and you’ve got it).

So that’s it for the active articulators! But they need to go somewhere in order to block air and produce a consonantal sound, which brings us to:

Passive articulators

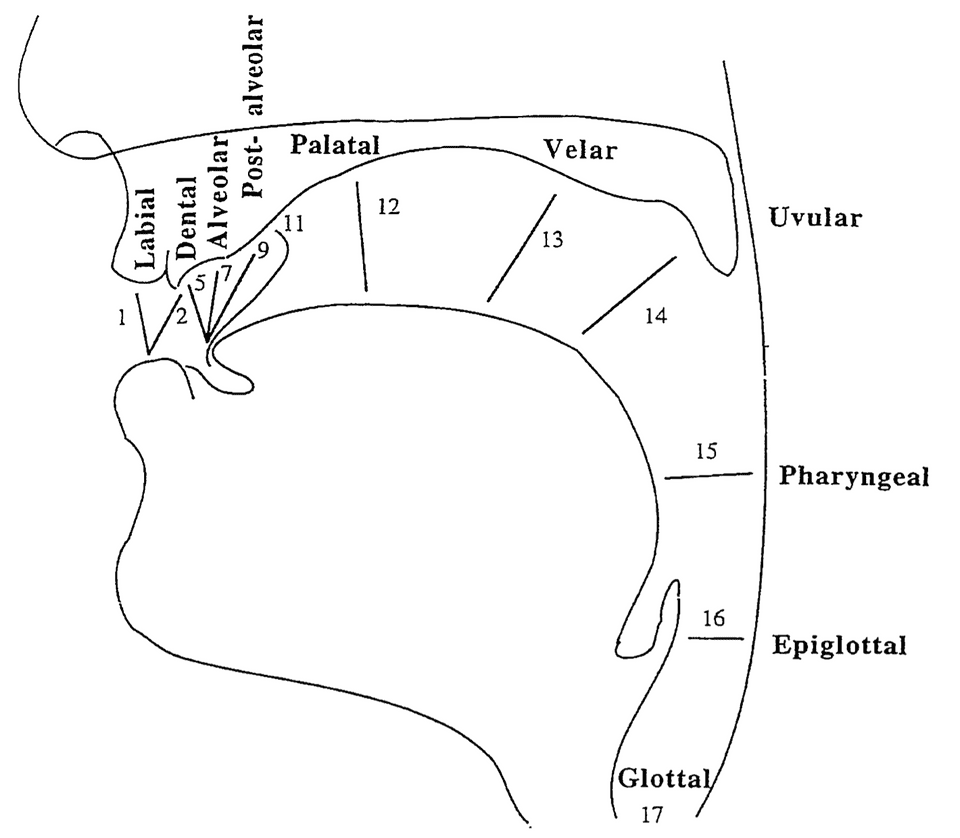

There’s about 9 (+ 1) regions where you can thrust those active articulators:

- the lips (labial),

- the teeth (dental),

- the alveolar ridge, that gummy ledge behind your upper teeth (alveolar),4

- the sloped part behind it (post-alveolar),

- the hard palate, most of the roof of your mouth (palatal),

- the soft palate, the back of the roof of your mouth, aka velum (velar),

- the uvula (uvular),

- the pharynx, the part of your throat behind the mouth (pharyngeal),

- and the epiglottis, the flap that makes food go down the right tube (epiglottal).

Finally, there’s also the glottis, the opening between your vocal folds (glottal).

By moving one (or more) of the five active articulators to one (or more) of the ten target regions, we end up with around 17 possible combinations where articulators can be brought together, forming the places of articulation for consonants in the table below. Note that the “English examples” are based on my dialect of English, and your pronunciation may slightly vary!

| Label | Place of articulation | Active articulator | Target region | English examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bilabial | Lower lip | Labial | /m/ as in "mat", /p/ as in "pat", /b/ as in "bat", /w/ as in "wet" |

| 2 | Labiodental | Lower lip | Dental | /f/ as in "fat", /v/ as in "vat" |

| 3 | Linguo-labial | Tongue blade | Labial | None |

| 4 | Interdental | Tongue blade | Dental | /θ/ as in "think", /ð/ as in "that" for some English speakers |

| 5 | (Apical) dental | Tongue tip | Dental | /θ/ and /ð/ (see above) |

| 6 | (Laminal) denti-alveolar5 | Tongue blade | Dental and alveolar | None |

| 7 | Apical alveolar | Tongue tip | Alveolar | /n/ as in "not", /t/ as in "top", /d/ as in "dot", /s/ as in "sing", /z/ as in "zip", /l/ as in "love" |

| 8 | Laminal alveolar | Tongue blade | Alveolar | None |

| 9 | Apical retroflex | Tongue tip | Post-alveolar | None |

| 10 | (Laminal) palato-alveolar | Tongue blade | Post-alveolar | /ɹ/ as in "row", /ʃ/ as in "ship", /ʒ/ as in "measure" |

| 11 | Sub-apical (retroflex) | Tongue underblade | Palatal | None; found in e.g. Hindustani and Swedish |

| 12 | Palatal | Body of tongue | Palatal | /j/ as in "yes" |

| 13 | Velar | Back of tongue | Velar | /k/ as in "cake", /g/ as in "good", /ŋ/ as in "sing", /x/ as in "loch" (from Welsh loanwords), /w/ as in "wash" |

| 14 | Uvular | Back of tongue | Uvular | None; e.g. /ʀ/ in French "restaurant" |

| 15 | Pharyngeal | Root of tongue | Pharyngeal | None; found in North Africa, the Caucases, and British Columbia |

| 16 | Epiglottal | Epiglottis | Epiglottal | None; found in Semitic languages |

| 17 | Glottal | Vocal folds | Glottal | /h/ as in "hope", /ʔ/ as in British "bottle" (the pause between the two syllables) |

Usually, the active articulators lie along the bottom of your vocal tract, and move to the passive articulators along the top. These places of articulation are shown by the arrows in the diagrams below:

You might be a bit surprised to see above that /w/ is a velar consonant. Isn’t it pronounced with the lips? Actually, /w/ is a great example of a consonant where the air is blocked in multiple places at once! These consonants with two places of articulation come in two different kinds:

- If air is blocked to the same degree in both locations, the consonant is called “doubly articulated”. These consonants occur mainly in Western and Central Africa.

-

More commonly, the consonant is mainly produced in one place, with coarticulation in a second place that obstructs the air less. Specifically, /w/ is a velar consonant with bilabial coarticulation.

- Theoretically, we can coarticulate any consonant by labializing, palatalizing, velarizing, or pharyngealizing it, using the respective superscripts in e.g. [kʷ] which appears in Cantonese, [ʃʲ] (aka [ɕ], the voiceless palato-alveolar sibilant) as in Chinese “xuě”, [lˠ] as in “full”, or [tˤ] which appears in Arabic.

Hopefully after messing around enough with your tongue, you should have a good sense of the different places in the mouth where consonants can be made. Now it’s time to move on to the next section of what makes a consonant: manner of articulation.

2. Manner of articulation

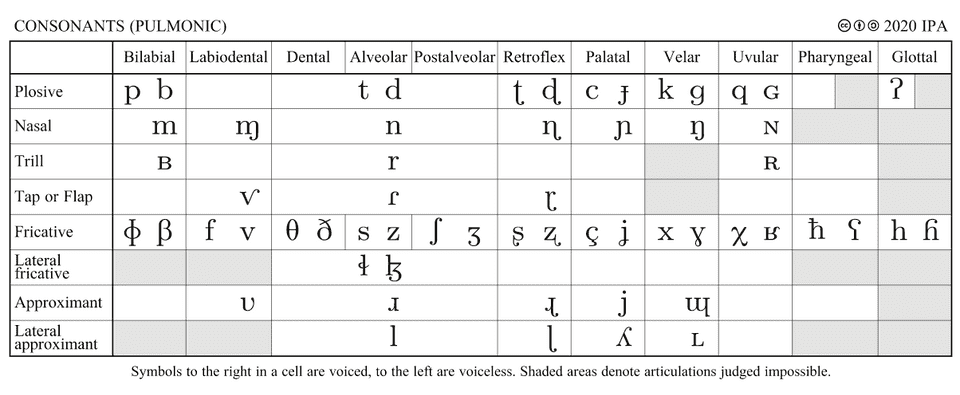

While place of articulation tells you where in the mouth a sound is made, manner of articulation tells you how much the air is obstructed. Roughly in order from totally obstructed to almost free-flowing, the manners of articulation listed on the 2020 IPA are (see above for the pronunciation of the symbols):

-

Plosive (aka stop)

- Stop air entirely, and then quickly released in a small puff of air

- e.g. [p], [b], [t], [d], [k], [g]

-

Nasal

- Air is rerouted through the nasal cavity

- e.g. [m], [n], [ŋ]

-

Trill

- An articulator is held in place, and air blown past it causes it to vibrate back and forth

- e.g. French [ʀ] or Spanish [r] or bilabial [ʙ] like blowing a raspberry with the lips

-

Tap or flap

- An articulator is thrown against another in a single gesture

- e.g. the middle consonant in the American pronunciation of “latter” [læɾə˞] or the Japanese “r” sound by most speakers

-

Fricative

- Air is almost fully obstructed, creating a hissing sound (aka “turbulent airflow”)

- e.g. [f], [v], [θ], [ð], [s], [z], [ʃ], [ʒ], [x], [h]

-

Lateral fricative

- An l-like sound where the tongue blocks the airflow through the middle of the mouth and air is pushed through the sides to create a hissing noise

- e.g. [ɬ], found in Icelandic, Welsh, and Navajo

-

Approximant

- No hissing sound; airflow only slightly impeded

- Aka semivowels/semiconsonants/glides (but these terms are not universally agreed upon)

- e.g. [ɹ], [j], [w]

-

Lateral approximant

- “l-like” sounds when the tongue blocks airflow through the middle of the mouth and redirects it through the sides

- e.g. [l]

Vowels would be at the very bottom of this list, where the air is essentially unimpeded, but we’ll save those for another post. Here are some other common terms related to manner of articulation:

- Sibilants are a specific kind of fricative (hissing sound) that have higher amplitude and pitch because the air is forced against the teeth, e.g. /s/, /z/, /ʃ/, and /ʒ/. They sound more intense, which is why they’re used often to get people’s attention, e.g. “psst!” and “shhh!”

- You’ll also hear about affricates, like the “ch” [tʃ] in “cheap” or the “zh” / “j” [dʒ] in “jeep”. These are made when you block the sound with a stop and then transition into a fricative.

- You can also group lateral (l-like) and rhotic (r-like) consonants into liquid consonants. Some languages allow these to take the place of a vowel at the nucleus of a syllable, as evidenced by the Czech/Slovak tonguetwister strč prst skrz krk.

Alright, so that’s it for place and manner of articulation! Now all that’s left is voicing.

3. Voicing

Voicing is simply whether or not your vocal chords are vibrating. For example, hold your throat (not too hard please) and say “fan” and “van”. You shouldn’t feel anything when making the [f] sound, but you should feel buzzing as you pronounce [v]. That’s how you can tell that [f] is unvoiced, while [v] is voiced!

Then you might ask: well, how can we tell the difference between them when you whisper, since whispering eliminates voicing? For example, try whispering the words “fan” and “van”. You should still be able to tell the difference, even though they’ve both become unvoiced bilabial plosives!

This is because the distinction between /f/ and /v/ in English isn’t just voicing; it’s actually called a fortis-lenis (strong-weak) distinction, which describes the amount of energy that goes into the sound. In English, all of the stops and fricatives (except for /x/ and /h/) come in fortis-lenis pairs.6

One of the distinctions between fortis and lenis consonants in English is aspiration. Hold your hand up in front of your mouth as you whisper “fan” and “van”. You should feel a little puff of air when you pronounce /f/, but nothing (or very little) as you pronounce /v/. In the IPA, we mark that puff with a superscript h, as in [pʰ] in “pick” vs [p] in “spot”.

There’s also diacritics we can add to modify the voicing of consonants and sounds. For example, we can add:

- The dot in [n̥] to make a sound voiceless, like in Icelandic;

- The dots in [a̤] to indicate a breathy voice (maybe avoid making this one in public);

- The wiggle in [a̰] to indicate a creaky voice, also known as vocal fry. Try speaking in a very low pitch and you should be able to hear each individual vibration of your vocal folds.

In the IPA chart, all of the symbols on the left in a cell are unvoiced, and the ones on the right are all voiced.

So after staring at this gobbledegook for long enough and making strange noises with your mouth for longer than you’d like to admit — ahem — you should know all you need to decipher each consonant in the IPA!

IPA Consonants

Here is the chart at long last:

You can also find a clickable chart here that will show you what these symbols sound like! As a little self-test of sorts, pick a symbol on the chart, see if you can guess its pronunciation based on everything you know, and then click the chart to see how close you were.

Typically, to describe a sound, we say the voicing, then the place of articulation, and then the manner of articulation. For example, now you should be able to pronounce the unvoiced palato-alveolar fricative from the start of this post! (Hint: it’s just the [ʃ] sound in “ship”.)

Conclusion

Well, that’s it for consonants 101! Actually, in hindsight, I probably put way more here than is strictly necessary to know about consonants at all. But on the other hand, there’s a ton of stuff I haven’t even included, like ejectives and clicks, which are less common in human language and which I don’t plan to include in my conlang since they’d be inconvenient for most people to pronounce. You can learn more about them in this Artifexian video!

Just to recap:

-

Consonants are a type of sound made by the obstruction of air. They’re defined by:

- Where they’re made (place of articulation),

- How much air passes through (manner of articulation),

- And whether or not they’re voiced.

Thanks for sticking around! This was a super long post, and don’t worry, as soon as we get into the actual conlanging, I promise we’ll dig into the fantastical, exciting worldbuilding stuff I know you’re waiting for.

Next time, we’ll cover vowels, which should be a much shorter post, and then after that, we’re all set to put together the phonetic inventory for the conlang!

See you around! Tschüss!

-

↩

But the inside of the mouth is continuous. How can we categorize sounds into distinct categories?

To answer this, let's consider two languages A and B. Let's say each of them have three distinct vowels that go from high to low (aka "close" to "open") in the mouth: language A has A1, A2, A3, and language B has B1, B2, B3.

Let’s say we get a language A speaker and a language B speaker together, and we find out that A2 is equivalent to B1, and A3 is equivalent to B2.

Then, that tells us that there must be at least four different vowels:

1 A1 2 A2 B1 3 A3 B2 4 B3 As we encounter more and more languages, we can begin to get a good sense of which sounds humans can distinguish.

-

↩

Phones [] vs phonemes //

For example, say the words "pun" and "spun", and pay attention to the "p" sound in both of them. Sound identical, right? They actually aren't! Put your hand in front of your mouth and try it again. You should feel a puff of air when you say "pun", but nothing (or very little) when you say the "p" in "spun".

The difference between the aspirated [pʰ] and the unaspirated [p] makes no difference in English; you can swap them without changing the word. Therefore, we would consider both of them the same phoneme, /p/. On the other hand, this would make a difference in languages such as Chinese, Icelandic, or Hindustani. For example, in Mandarin Chinese, “爸” [pa] (father) and “怕” [pʰa] (fear) are different words, and /p/ and /pʰ/ would therefore be considered different phonemes.

In IPA, we use brackets [] for phones and // for phonemes.

-

Note that I didn’t say “all sounds producible by humans”, since there’s also sounds like what you might find in beatboxing or licking your lips that don’t feature at all in human language. Also,

↩Why not just use the English alphabet?

First of all, there's a lot of sounds that English simply doesn't have, like retroflex or epiglottal consonants.

Also, English is actually an extraordinarily awful language when it comes to spelling, simply because our words come from so many different other languages (Latin, French, German, Norse, to name a few) so we never really had a consistent spelling system to begin with. The fact that spelling bees even exist attests to that! (Many places don’t have them because the spelling is actually consistent — you know, like it should be.)

The main issue is that there’s not a one-to-one mapping between sounds and letters. Heck, even our vowels (a, e, i, o, u) aren’t even pure vowels, they’re diphthongs, except for “e” ([eɪ], [i], [aɪ], [oʊ], [ju])! In total, English and its various dialects actually has around 25 vowel sounds (12 monophthongs, 8 diphthongs, and 5 triphthongs (like the British “hour” [aʊə])), which is a sheer absolute monstrosity. Japanese only has 5 monophthongs! Beautiful!7

The IPA fixes this by having distinct symbols for all sounds which humans can use to distinguish between words (i.e. phonemes). That being said, the IPA is meant to synergize with the Latin alphabet, so most of the Latin alphabet symbols are pronounced the same way they are in English.

-

Note that “alveolar” only denotes the front part of the alveolar ridge, i.e. the flat part right behind your teeth. The sloped part behind the ridge is the post-alveolar region.

↩ -

More precisely, “denti-alveolar” describes sounds where the tip of the tongue is against the teeth and the blade is pressed flat against the alveolar ridge. These sounds are very similar to their apical alveolar equivalents. In her 1991 Ph. D. thesis, Articulatory and Acoustic Properties of Apical and Laminal Articulations, Sarah Dart did research showing how native speakers of some languages including English and French use these and their apical alveolar equivalents somewhat interchangeably.

↩ -

The way different languages deal with this aspirated/unaspirated, voiced/unvoiced distinction is super interesting! For example:

- English uses fortis (aspirated + unvoiced) / lenis (unaspirated + voiced) as described above;

- French has no aspirated consonants, so the difference between French /p/ and /b/ is just voicing;

- Chinese makes no distinction between voiced/unvoiced, and instead uses /pʰ/ and /p/ as its two bilabial stop consonants;

- And Hindustani is especially detailed, with four distinct phonemes /p/, /pʰ/, /b/, and /bʰ/!

-

Is this a footnote within a footnote? Yes. Anyways…

“Wait”, you might be asking if you speak Japanese, “but there are diphthongs, like in “家” (/ie/, “house”)“! I should clarify: here I’m talking about diphthongs phonologically, which is defined as the case when two vowels share the nucleus of a single syllable (I’ll talk more about this in my post on phonotactics later). In this case, /ie/ would typically be considered as two distinct syllables (although this is a bit of a poor example since it’s debated whether or not Japanese has syllables at all, and instead uses “mora” to measure timing — ohmygoshihavetowriteapostaboutthisnow). Labelling “consecutive distinct vowels” as a diphthong or triphthong doesn’t tell us anything about how vowels are actually used in a language.

↩